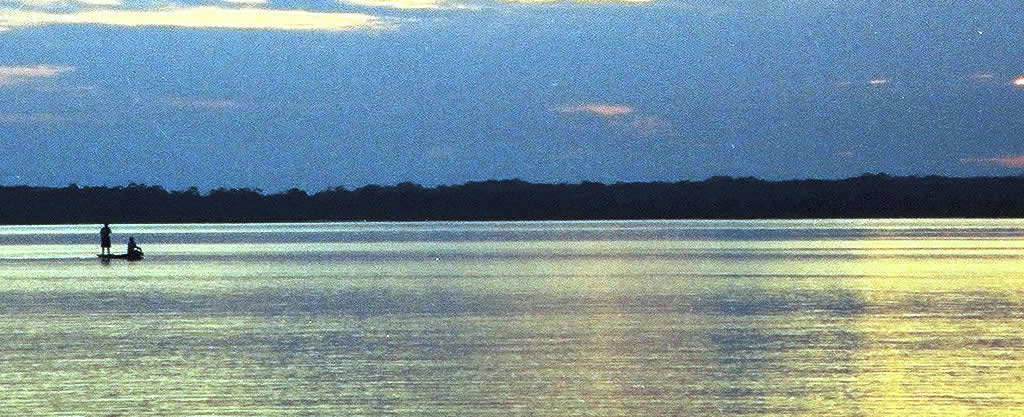

The flight from Chiclayo offers stunning views over the Andes and a glimpse into the endless expanse of the Amazon Rainforest. Inaccessible by road, Iquitos is a large city set in the middle of that jungle. Apart from the laid-back atmosphere and the friendliness of the locals, the first thing we notice are the unmuffled motor-taxis blaring their horns down every street. The second thing we notice is the river. At twilight, the silent water turns from pink to silver, and fishermen wave to us from their boats.

Fishing on the Amazon River at Iquitos

The next day, we board a speedboat that takes us eleven hours downstream to Tres Fronteras where Peru and Colombia meet Brazil. The twin outboards guzzle fuel and belch fumes as they chug their way along the river. The boat ride includes a cold and inedible lunch. Hopefully, the fish like it.

After exit formalities in Santa Rosa, Peru, and a taxi ride from Tabatinga, Brazil, we are in Colombia. Unplagued by drugs, guerrillas and kidnappings, this remote part of the country has a lazy river feel and vibe. We stay in Leticia long enough to organize a four-day excursion into the jungle and, in the morning, return to Brazil and board a launch at Benjamin Constant that takes us up the Javari River. We are technically back in Peru now.

Diane gets the window seat on an Amazon speed boat

Javari River and Zacambu Lodge

We are greeted by our host and guide, Jorge, while his wife prepares lunch for us. The Zacambu Lodge sits on the Javari River, a few hundred meters upstream from Lake Zacambu, and is built to accommodate thirty people, but we are the only two there. After a rather uninspiring lunch of overcooked fish and bland yucca, we set off towards the lake.

Among the mangroves lining the lake, we bait our hooks, and beat the water with our fishing poles. Jorge yanks his rod after a nibble and produces a piranha. He demonstrates the effectiveness of its sharp teeth on a leaf and releases it unharmed. I yank my rod after a while and produce an unbaited hook.

A Pink Dolphin surfaces for a breath on Zacambu Lake near the Javari River

For every five fish extracted by Jorge, we catch one. After a while, we abandon the angling and drift down the lake to where it meets the river – a favorite feeding area of the pink and grey dolphins. We spend an hour admiring these mammals as they surface all around us while dusk sets in.

After a dinner much like our lunch, we walk along a boardwalk to a dock on a small lake behind the lodge and climb into a couple of dugout canoes. We are told that the Javari River is safe to swim in, but are warned against swimming in this small lake. Some caimans (relatives of alligators) can grow to several meters in length. Muy peligroso

Diane poses with a baby caimen

With a powerful headlamp strapped to his forehead, and strange guttural sounds emanating from his throat, Jorge leads us on a caiman hunt. Sweeping the beam of light along the shore reveals a small reflection – a reptilian eye.

We paddle towards it, but as we approach the creature slides under the surface of the water and disappears. We circle the lake searching for more, but the animals vanish as we come too near.

Jorge is finally successful in catching a very small one with his bare hands. It is released and we continue looking for another one. We see a glint of something in a bush beside the shore, and upon closer inspection we discover … a beer can.

We are discouraged by the mustiness of our room and the unwelcome cockroaches, but are put at ease when Jorge appears with two mosquito net-rigged hammocks and begins stringing them up under the roof of the lodge’s deck. These will be our beds for the next three nights from where we can hear the dolphins surfacing and breathing.

The jungle is a noisy place at night, even after the generator is turned off. Once accustomed to our hammocks and the strange noises coming from the bushes around the lodge, the chatter and chirping of the frogs and insects eventually lull us to sleep.

Everything but the Carbon Sink

The Amazon Rainforest is the planet’s largest carbon sink. This vast expanse of vegetation converts 25% of the world’s carbon dioxide into oxygen and carbon. The oxygen is released into the atmosphere and the carbon is stored in the trees and other plant-life. When the trees and plants die and rot, they slowly release their carbon back into the atmosphere.

“Let us keep the dance of rain our fathers kept

and tread our dreams beneath the jungle sky.”

– Arna Bontemps

But, when jungles are deforested by slash-and-burn methods to make way for clear-cuts, cattle ranches and gold mines, as is being done rampantly in the Amazon, all that stored carbon is released immediately. As a result of these destructive practices, the Amazon’s ability to retain carbon decreased by over 30% from the 1990s to the 2000s. Amazon deforestation has only increased since then, and it is feared that the rainforest may become a net-emitter of carbon, rather than the carbon sink it has always been.

To further exacerbate the problem, some scientists speculate that the increase in carbon in the atmosphere is accelerating tree growth and leading to earlier maturity and death. Also, the scorched ground of the burned forest, compounded by more frequent droughts caused by climate change, is leading to higher temperatures and less water. The combination of these factors point to a grim future for the Amazon rainforest.

Amazon Anteater

We are up just before dawn, and after breakfast Jorge takes us down the river to a trailhead that leads into the rainforest. Jorge spots an anteater and chases it down before it can scamper up a tree. He harasses it briefly by prodding it with a stick while we take a few photos, and it runs away unharmed.

Suddenly, he starts running through the thick undergrowth, but we cannot keep up. He has spotted a monkey. Apparently, when chased, the monkeys become motionless (with fear?). It seems this monkey is unaware of this expectation as any evidence of its existence is, well, non-existent.

Jorge cuts one of the many roots and vines hanging from the treetops, and offers us a drink of the water dripping from it. We marvel at the massive Victoria lillypads growing in the swamps throughout the forest, and wade chest-deep through these same swamps, tight roping along unseen tree roots under the water. He slaps the water with the flat side of his machete to scare off anacondas and other serpents, or perhaps to attract them. Muy peligroso.

Native Populations and Tree Huggers

We find ourselves back at the boat and are shortly enjoying more overcooked fish and bland yucca for lunch. We spend the afternoon motoring upriver to the “traditional” village of November 3rd – presumably the town’s founding date. There, we find a church, generators, T-shirts, chainsaws and polygamy, which reinforces the notion that cultural differences are becoming scarcer, and also reinforces our desire to see as much of the world as we can, now.

Uncontacted Amazon tribes and villages can only be visited with a special government research permit. The native inhabitants were once protected from outside influence and disease for good reason. Tragically, a recent news story describes the murder of several tribes-people by Brazilian gold miners in this region.

Comunidad 3 de Noviembre on the Javari River

The next morning brings rain, but this is, after all, a rainforest. Happily, shortly after breakfast, the weather begins to cooperate and we embark on another jungle hike. Along the trail, Jorge points out various trees and explains their use and significance.

We turn our heads to protect our faces as Jorge cuts a gash into a large trunk with his machete. The milky sap of the tree is very poisonous and will cause instant blindness if it comes in contact with one’s eyes. Muy peligroso. Local fishermen put it in the water because blinded fish are apparently easier to catch. Another tree’s bark contains quinine which can be used to treat malaria.

Jorge shows one of the many rubber trees that he assures us have brought “mucho dinero y muchos muertes” – much money and many deaths – to the region. Lucrative rubber plantations started deforesting the Amazon in the 19th century, and the indigenous people were enslaved to work the crops.

Many were tortured and killed with some reports indicating that as much as 90% of the local population was killed during the rubber boom. Rubber plantations are monocultures and the antithesis of biodiversity that eventually lead to a collapsed ecosystem and an unsustainable industry. Today, the violence against those who try to protect the Amazon continues. Indigenous and environmental activists are being targeted and killed by players poised to profit from the pillaging. A few weeks ago, an indigenous activist was murdered in the Tres Fonteras area.

Diane bangs on a “Jungle Drum”

Alex swings from a tree vine

After a while, we are convinced that Jorge has gotten us lost. As we are on the verge of despair, he shows us what he brought us there to see – the biggest tree in this part of the jungle. And, it is by far the biggest tree we have ever seen. It measures nearly ten meters from one end of its buttressed trunk to the other. It would take at least a dozen hippies to hug this tree!

We are awestruck as we walk around it. Jorge tells us that locals would communicate with each other across the vast forest by banging on the trunk of such trees – Amazon smoke signals. After a few Tarzan swings from its vines, we head back to the boat.

Feedlots, Forestry, Phosphorous and Fires

The Amazon Rainforest has been under attack by private, industrial and commercial interests for a century. Corporate food giants have been razing the jungle to make way for illegal beef and cattle ranches to fill the gullets of fat and lazy consumers and pad the profits of leather markets. About 2500 illegal mines dot the Amazon, excavating the forest and poisoning the water with tailing chemicals. Illegal logging and road-building further deforests and already fragmented landscape.

Jorge stands over Victoria Lilypads

To convert CO2 to carbon, a forest needs fertilizer. Unlike temperate forests that use nitrogen as fertilizer, tropical forests rely on phosphorous. At nearly 80%, nitrogen is the most abundant element in the atmosphere. On the other hand, phosphorus is stripped from rocks and transported to ecosystems downstream.

But, Andean glaciers have slowly stopped transporting phosphorous to the Amazon valleys long ago. The concern is that the carbon-sequestering ability of the receding forest will further decrease with a limited phosphorous supply.

Currently, the most dangerous threat to the Amazon rainforest are the fires that continue to rage across the jungle. These fires are set to clear the forest for illegal industrial development and are now burning out of control. Brazil has been the target of much international criticism for its response to the fires and its recent rollbacks of environmental regulations preserving the Amazon and its native people.

Instead of further protecting this global asset, Brazil has signed an agreement with the United States to allow more industrial development deeper into the Amazon. But, part of the agreement is also to set aside $100 million for a private sector-run “biodiversity and conservation project” to be conducted over 11 years. To put that absurdity into perspective, $100 million is the annual salary of 6-7 average CEOs, and the Amazon’s carbon sequestration decreased by a third in about 11 years.

Digging the Dugout

Alex paddles a Dugout Canoe

It starts to rain, again. Actually, it is a torrential downpour and we are soaked to the skin. We are even wetter than our swim through the swamps on the previous day. Eventually, the rain stops, but no sooner does it stop than the mosquitoes return – in earnest. If we stop running, we are swarmed.

Harboring an unfulfilled desire to explore the tributaries of the Amazon in a more natural way, we borrow the lodge’s dugout canoe and head down one of them. We paddle as far as we possibly can, and savor every moment.

Returning to the lodge, we realize that there is still time before dusk, and continue to Lake Zacambu. Again, the dolphins are everywhere. We sit in the canoe and some even swim under the boat, partially lifting it out of the water.

Dawn of our last morning finds us paddling to the lake to enjoy the jungle at daybreak. Egrets, kingfishers, ducks, parrots, and birds of all colors abound. We finish breakfast and motor across the river to Brazil, where we try piranha fishing again and enjoy the same luck as our first outing.

Three flags adorn our Javari riverboat

Amazon River and Rainforest

After one last meal of overcooked fish and bland yucca, Jorge piles us and his family into the launch and sets off for Benjamin Constant, where the Javari River meets the Amazon. We say our thank yous and goodbyes, and retrace our steps back to Iquitos and the Peruvian coast.

Accelerating deforestation, forest degradation, and drought in the Amazon is of great concern to scientists who warn that the entire biome may be near a tipping point where large areas of wet rainforest could transition to dry tropical woodlands and savanna. Such a transition could have dramatic implications for regional rainfall, with the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone potentially shifting northward, leading to drier conditions across South America’s breadbasket and major urban areas. The impact on regional economies could be substantial, while the impact on ecosystem function and biodiversity of the Amazon could be devastating, according to researchers.

Thank you for the insight Cameryn.

According to this article from December 2019 (https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/12/eaba2949), “The only sensible way forward is to launch a major reforestation project especially in the southern and eastern Amazon, actions that could be part of Brazil’s implementing its commitments under the Paris agreement.”

Unfortunately, applying this suggestion to reverse the deforestation/drought feedback loop seems very unlikely considering Brazil’s current political climate.

Spent a very memorable week with Jorge… in 2004. Looks like not much had changed in 15 years!

Hi Alex. Thanks for the comment. We cannot confirm nor deny if things at Zacumbu have remained the same for the past 15-20 years. Our story is based on a trip we took there in December 2003, prior to your visit.